This blog is an extract from the book John Bradburne: Soldier, Poet, Pilgrim. A Secular Franciscan from Cumbria, Servant of God John Bradburne poured himself out in love for the lepers he served, unwilling to abandon them even to save his life. His legacy offers a striking example of authentic holiness in the modern, conflict-stricken world.

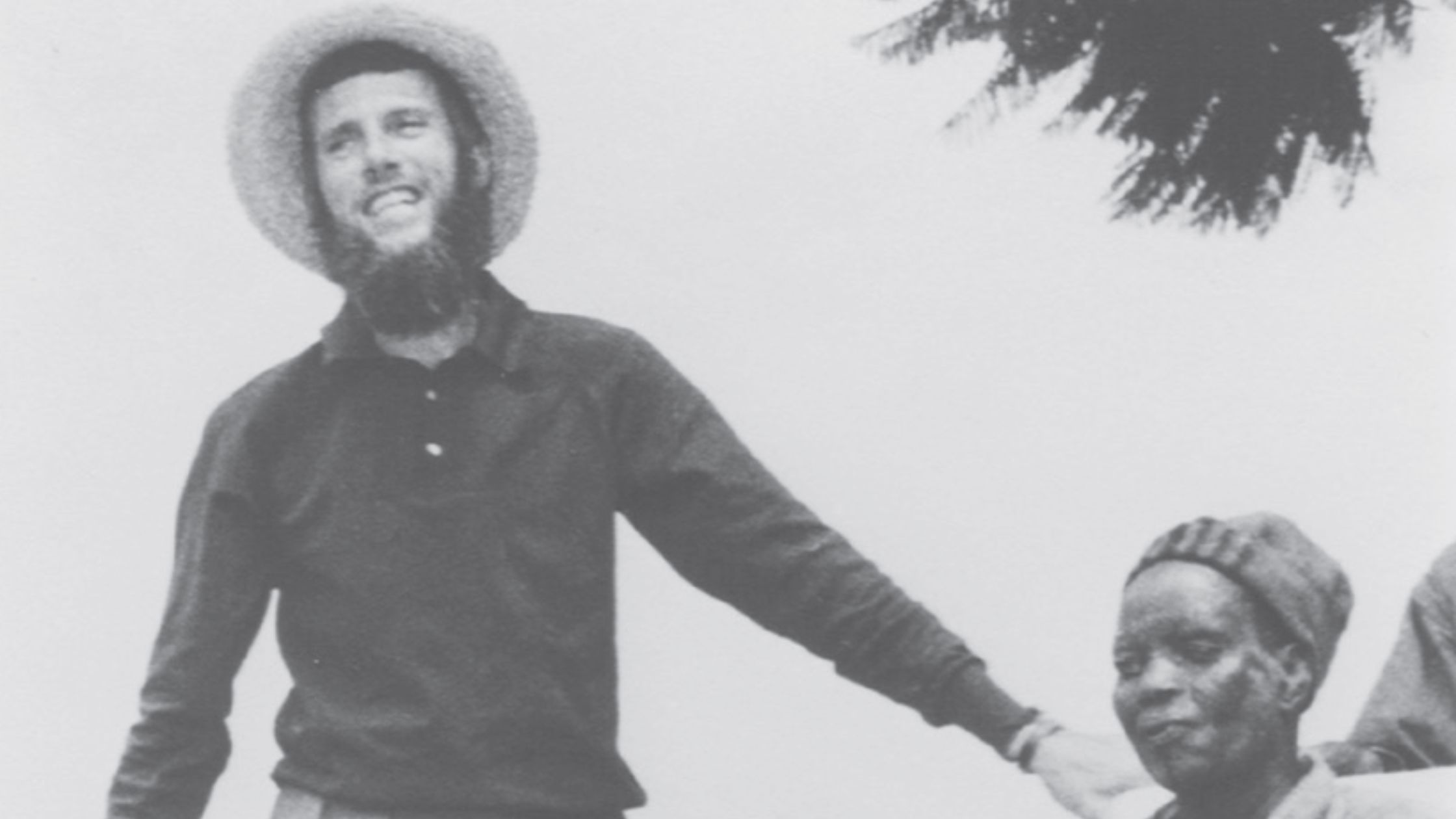

In March 1969 a good friend of his, Heather Benoy, invited Bradburne to join her as she set out to investigate a leper camp eighty seven miles north-east of Harare. Benoy had heard accounts of atrocious conditions at the camp and wanted to discover whether the reports were true. The camp was called Mtemwa, a Shona place name that

could be translated as ‘you are cut off’.

Mtemwa, forty years earlier, had been home to over two thousand lepers but, by the late 1960s, medical advances had allowed most lepers to return to their homes. In 1959 those in the community at Mtemwa who had been cured of leprosy but had remained in the camp were ordered to leave. Despite this, some two hundred remained in the camp, mainly those who had been left severely deformed by the disease. These victims either refused to leave to face discrimination and mockery in their home villages or simply were unable to leave. By 1969 the ravages of neglect and abuse by those in charge had reduced the camp of some eighty or so souls to lives of squalor and misery.

Benoy and Bradburne arrived at Mtemwa driving through an avenue of mature jacaranda trees. Their first sight was of a modest house and, beyond that in the verdant greenery of the rainy season, they could see the lepers’ huts. As they walked towards these huts the horror of what they had heard of the place became real: hideously deformed men and women, their faces and limbs contorted by their shared dreadful disease, their fingernails dislocated, their bodies filthy and covered with untreated sores. On seeing the unexpected visitors, the lepers retreated to their huts only to re-emerge with sacks or blankets over their heads. As one crawled through the mud on all fours, Bradburne could only utter, in total disbelief at the hell that he was witnessing, “My God! My God!” Disbelief turned to anger as he learnt that the lepers had been ordered, by the director of the centre, to cover their faces if any visitors came to the camp, and as he saw an elderly lady covered in mud and licking a bowl on the ground.

EMOTIONAL TURMOIL

Disgusted and intending to report what she had seen, Benoy was desperate to leave the camp and return to Harare to report the conditions to the authorities. Bradburne, however, resorted to his tried and tested way of discerning the will of God: he prayed, tossed a coin in the air to decide what to do next, and declared that he was going to stay. Benoy could not believe what she was now hearing and begged Bradburne to at least return with her to explain the situation to Fr Dove and collect his belongings. Finally, Bradburne acquiesced, and agreed to return. Bradburne was in emotional turmoil. Back in Harare he talked through his conundrum with John Dove who later recalled his friend’s words at the time:

You know, I don’t think that I could be very useful at Mtemwa because I’ve never been a boy-scout. I don’t know anything about medicine, and they are in a very, very poor and serious state. They are dying of neglect. They have been treated appallingly. At any rate, I’m a reject, they are rejects, so I think we will understand each other… And so I go down on that ticket.

Almost immediately upon arriving back in Harare Bradburne distilled into verse his feelings:

In that I’ve always loved to be alone

I’ve treated human beings much as lepers,

For this poetic justice may atone

My way with God’s, whose ways are always helpers;

I did not ever dream that I might go

And dwell amidst a flock of eighty such

Nor did I scheme towards it ever,

The prospect looms not to my liking much […]

Bradburne prayed for strength to follow what he was convinced was a calling from God for him to care for the lepers of Mtemwa. Meanwhile John Dove made inquiries

into who was responsible for the camp. He discovered that in 1966, a retired farmer from Harare, Philip Dighton, had visited Mtemwa and was also appalled by what he discovered. Dighton made contact with the Jesuits and, together with a Jesuit priest, Edward Ennis, an agreement was drawn up with the Department of Labour and Social Welfare, the government department that had oversight of the camp, so that the Archdiocese of Salisbury could, backed by government finances, restore the camp. A committee was set up to fundraise for any expenses that were incurred that went beyond the agreement with the department.

Dove discovered that the Jesuits had been trying, but had failed, to find a new caretaker for the camp. Dighton and Bradburne met after which Bradburne was appointed Camp Superintendent of Mtemwa and given a small salary. Among his duties Bradburne was in charge of bookkeeping, responsible for the camp’s orderlies and other administrative duties – aspects of the job that he knew that he would hate and believed himself hopelessly incompetent at fulfilling. Yet if this was the personal cost, Bradburne was more than ready to pay the price.

At first Bradburne was adamant that he would live in one of the leper huts and even went as far in his desire to identify as closely with those for whom he was to care as expressing his hope that he too might catch leprosy. When informed that if he did succumb to the disease he would be moved to a European leprosarium, he finally agreed to lodging in a refitted butcher’s shop on the edge of the camp. On 1st August 1969 John Bradburne moved to Mtemwa – he was to remain there until his death.

Upon arriving at his new home, Bradburne set about learning the names of the seventy eight lepers at the camp and introduced himself to Dr Luisa Guidotti and the

religious sisters who were stationed at the All Souls Mission eleven miles north of Mtemwa and were responsible for the medical needs of the camp. Two weeks after arriving at the camp, Bradburne wrote frankly to his mother about the stresses and strains of his new life, admitting to having just downed a triple brandy after a particularly trying day but asking her to pray hard, “that drink NOT my consolation be.”

DAILY LIFE IN THE LEPER CAMP

Each of Bradburne’s days at Mtemwa were structured by his singing of The Office and his daily recitation of the Rosary. At the heart of his main room he constructed, from boxes, cartons and tins, what he referred to as his ‘Ark of the Covenant’. The ark was built in the shape of a pyramid and was covered in rosaries, crosses, shells, cards, ribbons, ornaments and pieces of paper on which Bradburne had written his poems. It was ever changing in its appearance as Bradburne added or subtracted various elements of its decoration. One element of this focal point of Bradburne’s devotion was the Bible that he reverently kept at the bottom of the pyramid. For Bradburne, calling the shrine the ‘Ark of the Covenant’ reminded him of the ark that was the most treasured possession of the people of Israel and contained the stone tablets on which the Ten Commandments had ‘been’ written. ‘Ark’ also reminded him of the Blessed Virgin Mary, one of whose titles is ‘Ark of the Covenant’ in reference to carrying the child Jesus, the very word of God incarnate, in her womb. To prayer, Bradburne added mortification, eating and sleeping as little as he possibly could and referring to his physical body as Brother Ass.

A priest that was based near Mtemwa and who became a close friend of Bradburne, Fr David Gibbs, recorded that a typical day for Bradburne would start at dusk with the chanting of The Office in his hut. Throughout the night, if not attending to a dying or very sick leper, he would pray and meditate and, “when the Muse came”, write poetry. Early in the morning he would run a mile, “just to keep fit,” before washing and going to open the chapel. A morning service would follow where prayers were offered, the scriptures heard and Holy Communion distributed, Bradburne also playing the organ for the service. Then, Fr Gibbs writes:

The voices die away, the organ stops, the doors of the church are opened and the lepers file out led by ‘Baba’ [father] John carrying a basket. As the lepers come out of the chapel, having just received the Body of Christ, they stop to chat to Baba John. Some just say ‘hello’, others ask for medicine for a headache, a cough, a cold, malaria, itching body or sore eyes. ‘Baba’ delves into his basket and produces a bottle, a tube, a few capsules, an ointment, a cream or just a few sweets for those who need cheering up.

There is something for everybody. Spiritually fulfilled, materially helped, the lepers move off to their huts happy, cared for and at peace with God and with each other. Some walk, others crawl and still others are wheeled away in wheelchairs.

SERVING THE SICK

After a light breakfast, Bradburne would visit every leper every day. He brought food to them and dressed their wounds; he washed those of them that were unable to do this themselves and cleaned the ground between their huts of rubbish; he carried those who could not otherwise move, gathered firewood for them and made them fires in the winter; with a wheelbarrow he went shopping for them in nearby Mutoko. When the lepers were sick he would sit with them, when they were dying he would stay with them all night and when they died he would bury them. Of one of his leper friends, he wrote:#

There is an old lady (called Marchareeda or Matilda) who has no eyes and no hands, and has until this month been feeding herself with her face in her plate much as an animal might. She cannot use a spoon. Of the food she was given, dogs and hens used to steal at least half, and a further quarter would be either spilled or smeared over her face and dress. So now I either feed her myself with a spoon, slowly, or if I am too busy with medical matters I get one of the orderlies to do it. It is great fun feeding her and she thoroughly enjoys it.

Bradburne would start each morning ‘round’ with a wheelbarrow full of gifts that he had been given to distribute among the lepers; nuts, sweets, tea, vegetables, tomatoes, bread, meat and much else besides. By the time that he returned to his chapel to pray the Angelus at midday, the barrow was empty. Fr Gibbs records:

After a period of quiet in the presence of the Lord, the afternoon would be spent in much the same way – cutting firewood, cleaning out the cattle grid, collecting reeds for making hats, making tea or coffee for the sick or just popping in to chat and cheer up the people. Once or twice a week John would go up to the village to do the shopping for the lepers.

For those really ill or dying, John would buy something special at the village – perhaps fresh oranges, an egg or two, an extra portion of milk or a pint of ‘real’ milk. On his return from shopping he would visit his ‘special’ patients – those seriously ill at the time – and help them to get their fire lit, bed made, pipe filled, coffee boiled or whatever other small tasks needed to be done. Sometimes he would simply crouch on his haunches and chatter away, trying to help and encourage.

The Rosary and evening prayers were said in the church at 4pm, allowing the lepers to gather for their evening meal at 5pm and Bradburne to begin his daily cycle of prayer once more.

In the midst of his labours, poetry flowed incessantly from Bradburne, each of his leper friends being captured in verse. He was able to share much of his poetry with a Jesuit who arrived at Silveira House in 1973, Fr David Harold Barry. On one occasion, he clearly instructed Harold-Barry to destroy any of his poems if he thought that they were not in keeping with the faith of the church.

VOCATION FOUND

An early poem from Bradburne’s years at Mtemwa expresses his awe and joy at the vocation that he had discovered:

This people, this exotic clan

Of lepers in array

Of being less yet more than man

As man is worn today:

This is a people born to be

Burnt upward to eternity!

This strange ecstatic moody folk

Of joy with sorrow merged

Destined to shuffle off the yoke

Of all the world has urged:

This oddity, this Godward school

Sublimely wise, whence, I’m its fool!

Be inspired by the humble, simple faith of a British man on his way to sainthood:

The life of John Bradburne reflects a struggle familiar to many people today: if you want to find God you need to search. Bradburne’s search, his life’s pilgrimage, took him from his birthplace in Cumbria through India, Malaya, and Burma during his soldiering years, and finally to Africa where he at last found God and his own sacred calling amongst the lepers in Mtemwa, Zimbabwe.

The life of John Bradburne reflects a struggle familiar to many people today: if you want to find God you need to search. Bradburne’s search, his life’s pilgrimage, took him from his birthplace in Cumbria through India, Malaya, and Burma during his soldiering years, and finally to Africa where he at last found God and his own sacred calling amongst the lepers in Mtemwa, Zimbabwe.

Led by a faith that he often expressed profoundly and poetically, John Bradburne followed the example of Christ, pouring himself out in love of the lepers he served, unwilling to abandon them even to save his own life as the violence of the Zimbabwean struggle for independence closed in around Mtemwa.

Remembered by those who knew him for his humility, simplicity, joy and friendliness, John Bradburne offers a striking example of authentic holiness in the modern, conflict-stricken world.

Order your copy of John Bradburne: Soldier, Poet, Pilgrim today