In the final days of Advent, the Church recites the Great O Antiphons at Vespers each evening. In this blog extracted from Praying the Great O Antiphons, Katy Carl reflects on the fourth of these O Antiphons: O Clavis David.

Gospel Acclamation:

Key of David, who open the gates of the eternal kingdom, come to liberate from prison the captive who lives in darkness.

Magnificat Antiphon:

O key of David and sceptre of Israel, what you open no one else can close again; what you close no one can open. O come and lead the captive from prison; free those who sit in darkness and in the shadow of death.

Reflection on O Clavis David

The imagery of this antiphon takes some work to unlock.

To the degree that we may tend to resist the idea that the guidance of an authority is necessary to salvation, even more are we likely to struggle with this image of locked gates between us and the “eternal kingdom.” To the extent that we are acculturated into a worldview that perceives God’s laws as arbitrary, or secretly sourced in human invention, we will have trouble with this image. I will try to articulate our common trouble as follows.

The first problem: If the only thing standing between us and eternal freedom is a gate, why do we need a key to the gate? Why a gate at all? Why doesn’t God just blow the gate off the hinges? Why does he seem to put up so many barriers, so many hedges, so many prescriptions and proscriptions, before we can access him? Shouldn’t access to God be simple and direct and clean, a movement of the heart without practical obstacle? Isn’t the process of growing into greater freedom, at its core, just a recognition that we are already radically free and cannot be forced into acts we do not agree with?

The second problem: How is the newborn, whose picture we are holding in our minds and who is the subject of all these antiphons, also somehow a key to anything at all? How do these helpless hands break us out of prison? To the extent that contemporary society sees newborns at all – for every new mother today knows in her bones that she, her newborn, and their shared needs are often socially invisible – it sees the newborn as a nexus of burdens, demands, obligations. And, in fairness, few new parents would describe having a newborn as freeing or liberating for themselves. Here again, we seem to have a mismatch in our imagery. (We might say, “This is difficult to visualise,” in creative-writing workshop terms.) When God sets out to liberate us, why does he so often do this in ways that seem at first to bind us more tightly?

The answer to both problems lies not with God but with us. God is simple, but we are not. We experience creation as a multiplicity, a “blooming, buzzing confusion,” – which, interestingly, is how philosopher William James described the experience of newborn children.14 This is because we live in medias res, in the middle of the story, which God set in motion at the beginning of time. Our point of view about the whole of reality is limited; our perception can take us only so far. We may as well take a moment here to imagine the point of view of the newborn Jesus himself: fuzzy lights, warmth, chills; smells of hay and animals and milk, and of the barrier of cloth between his arms and the air; the blurry faces of Mary and Joseph and, farther away, of all those strange large bipeds his fragile human body knows only as not-Mary and not-Joseph. We don’t often realise what a breath-taking act of self-emptying, or what theologians call kenosis, this represents. We can tend to process, and maybe even psychologise, the Crucifixion as a piece of sublime heroics, as noble self-sacrifice for the good of others, but above all as an act of mature agency: something Jesus allowed to fulfil his Father’s will. It’s harder to imagine what a sacrifice of agency and even autonomy the Nativity itself represented. Why, if one could help it, as only God could have helped it, why choose such a total, radical limitation, such a willed reduction of infinite capacity? The ablation of one-eyed Odin is, forgive me the pun, not a patch on this. To accept our own radical, existential interdependence with others is, culturally and personally, far harder for many of us than any act of independent self-assertion could ever be. Here too, Jesus is our model, and all he must do to lead the way is consent to having a heartbeat. This may seem minimal, but it is no small thing.

To return, though, to considerations about our own point of view: We value our perception so deeply and so highly because clarity of mind and vision is the ground of our beloved agency and autonomy. Our perception even makes moral claims on us, as it truly seems to present things in their wholeness. It gives us light, but not all the light we need. If we steer by our solitary perception alone, we will find ourselves adrift. To clarify the confusion, we need boundaries. The more intense the human desire involved, the stronger and clearer the boundaries need to be.

This is why the Ten Commandments, and the habits and practices by which we conform to them, are not arbitrary but deeply ordered to our good. God’s authority arises from his being the author of our human nature. He wrote his law into our hearts at our creation. Close attention to experience and to science, to every kind of possible human knowledge, can only in the end lead us closer to him, as “truth cannot contradict truth.”15 In making us the kind of creatures we are; not ‘ghosts in a machine,’ but matter-and-spirit unities, the kind of bodies we are, suspended inside the souls that animate them – in making us this way, God is not locking us into some miserable jail cell, from which we are only to be released at our physical death. The human body is a shelter, not a prison; a temple, not a cage.

In this situation, the Son-of-God-become-Man is an interpretive key as well as a literal one, capable of bringing us mental, emotional, and spiritual freedom as well as more immediate and obvious kinds of physical freedom. Contrary to our intuition, perhaps, this inner freedom must precede and inform the ever-greater degrees of external freedom to which it should lead everyone who embraces it. That maintaining this inner freedom requires our self-restraint should be no surprise to anyone who has ever pursued a discipline of any kind – sport, art, business, research, education, or any other human endeavour. If we follow such disciplines, we discover things we may not do if we want to succeed, things that are incompatible with our goals.

In Catholic tradition, we describe sin as imprisonment, even as slavery. This is fraught language, conjuring images of cruelty and evil, and a history in which oppressors, many of them Christians, failed to honour the demands of human dignity for all, so it is worth taking time to ask what it really means. In what does this imprisonment, this slavery, consist? St. Paul touches the core of the dynamic when he writes, “I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate” (Rom 7:15). Few people reach adulthood without having at least some experience of this human tendency to ‘self-destructive acts’. A still more vivid way of looking at this question, specifically, of looking at the positive vision of human freedom Catholicism proposes instead – is shaped by the ideal of holy poverty, embraced by generations of saints. This ideal recognises that whenever we put our own desires first, we tend to enslave ourselves to our own appetites. Turned in on themselves, our real needs become distended with bloat, distorted by accretions, until we now feel we ‘need’ things we once only wished for and come to crave things that sicken and weaken us. In this paradox we see that those who oppress others are often, themselves, at least equally trapped and oppressed by their own tendency towards evil, expressed in self-centeredness. Bound by their own extraneous and exorbitant demands to be served, to be pleased, and to have their sweeping visions carried out at any cost, they cannot even access the spiritual freedom that remains available to those they oppress. Without offering others real freedom, it is impossible to attain one’s own liberation.

By contrast, holy poverty does not mean destitution; it is, instead, a willingness to be satisfied with sufficiency, what author Haley Stewart has called “the grace of enough.” Religious orders and consecrated persons have long instantiated this ideal, and many throughout history have made a virtue of necessity by finding ways to thrive on fewer resources than most of us would consider liveable. This might seem like a digression, but it is relevant because the Holy Family was almost certainly among this multitude of those who have made their way through the world on just enough. Scholars have pointed for evidence to the two turtledoves offered by Mary and Joseph on the occasion of Jesus’s circumcision in the Temple, in place of the more elaborate sacrifice usually brought by wealthy families. As a working artisan, Joseph would have earned a liveable and respectable income, but he would not have been affluent. And as an adult, after giving up his own workshop for his ministry, Jesus had “nowhere to lay his head” (Matt 8:20), famously telling his disciples to pack nothing more for travel than a staff and a pair of sandals – no food, money, or extra clothing allowed (cf. Matt 10:9-10).

While Christ does not call everyone to such total austerity, it remains tragic and needless to let so many in our society be deprived of daily needs, while others indulge in overwhelming excess. Justice calls us to find ways of being attentive to the needs of others. Wendell Berry asserts that, in order to establish justice and preserve resources for the future, the privileged “must achieve the character and acquire the skills to live much poorer than we do.”16 Thoreau, disciple of secular monasticism, writes: “A man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone.”17 This line of thought finds its consonances in the Christian tradition, stemming from the examples of Joseph, Mary, and Jesus themselves: When we put the common good first and choose to live simply in terms of meeting our individual needs without excess, we find ourselves more free than when we are weighed down by literal tons of possessions that require maintenance, waste that ruins nature for future generations, and useless troves of luxuries that may amuse but cannot benefit us in the long term. Freedom, by contrast, comes only with the possession of “treasure in the heavens that does not fail, where no thief approaches and no moth destroys” (Luke 12:33).

In the language of faith, by contrast, the accomplishment of freedom is the attainment of a vision of the way God intended us to be free. Without our works of freedom, which are linked to our works of kindness to others, our faith in that vision is dead (cf. James 2:14-17). At the same time, paradoxically, this vision, this freedom, always keeps its ultimate nature as a gift, a grace. Under our own power alone, we are completely incapable of ever perfectly fulfilling it. However much effort we put into the work of kindness, our ability to perform generosity and the very things we give are always granted to us. No action of ours, no lifetime of actions, can ever fully deserve such fulfilment.

All the merit is on God’s side, but God is a better and more generous giver than any human person can be. He does not attach strings. What he gives us, he gives us as our own. He will offer us all the grace we need, but he will never force us to co-operate with it. If we choose to misuse our freedom, we will miss the mark, and we will lose liberty and possibly even life itself. On the contrary, if we put our freedom to work for the good in a spirit of wholehearted love, we will find ourselves ever more deeply involved in kinds of freedom we never expected, freedoms from and freedoms for: freedom from hatred, from falsehood, from fear, from insatiable desire; freedom for excellence, for peace, for joy, for “the grace of enough.”

How does the infant Christ, born into our lives and suddenly seeming to make a thousand new demands on us, involve us in these freedoms? We could ask this question another way, like the riddle it is: When is a newborn also a key? When he is an interpretive key: when what he stands for, what he instantiates, unlocks a prison in our minds. When the service of his needs – which present themselves to us as the needs of the people in our lives – liberates what is better in us and casts away what is worse. When he opens the door of our self-centeredness, a trap whose gate only ever locks from the inside, and invites us to walk out into our authentic strength. When he breaks us out of the prison of egotistical desire by transforming desire itself. When he gives us the power and liberty to be generous because God is generous, patient because God is patient, and loving because God is loving. He does all this most completely through his own Passion, Death, and Resurrection, but his birth sets the possibility of these events in motion; even in his infancy, his Incarnation already involves him in the work of redemption and us in the freedom of the children of God. If this liberty paradoxically binds us, it does so as a security against the dangers of self-absorption and self-deception. These are dangers to which no one is immune. As much as we are protected from them, to that same extent we can truly exercise our fullest freedom.

Image copyright Fr Lawrence Lew OP.

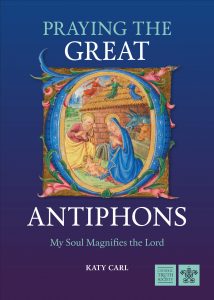

This blog is extracted from our book Praying the Great O Antiphons. In the final days of Advent, the Church recites the Great O Antiphons at Vespers each evening. Katy Carl contemplates each of these antiphons, drawing on art, literature, and Sacred Scripture to show how they tell the story of Jesus Christ, the Babe of Bethlehem.

This blog is extracted from our book Praying the Great O Antiphons. In the final days of Advent, the Church recites the Great O Antiphons at Vespers each evening. Katy Carl contemplates each of these antiphons, drawing on art, literature, and Sacred Scripture to show how they tell the story of Jesus Christ, the Babe of Bethlehem.

To learn more about the O Antiphons, order your copy of Praying the Great O Antiphons today.