The argument that is often made in favour of trans women competing in women’s sports:

It’s unfair to discriminate against trans athletes. Research of sports medicine demonstrates that there is “no direct or consistent research suggesting transgender female individuals (or male individuals) have an athletic advantage at any stage of their transition”. But even if they did, Lia Thomas rightly remarked, “It’s not taking away opportunities from cis women, really. Trans women are women, so it’s still a woman who is getting that scholarship or that opportunity.”

Reply:

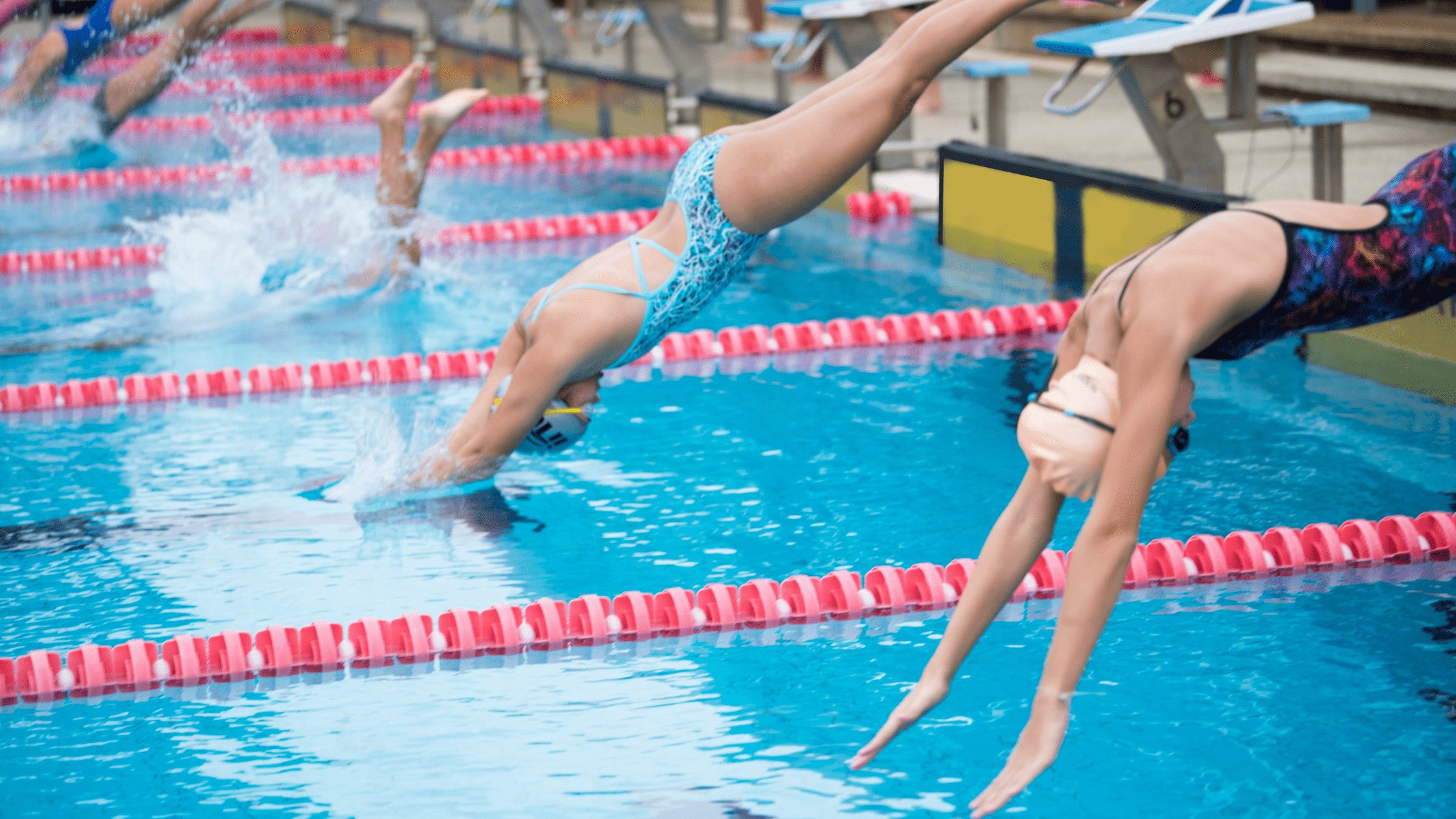

In 2022, Lia Thomas—who had competed on the men’s swim team at the University of Pennsylvania for three years without significant success—shattered the women’s Ivy League record in the 100 free, beating out Yale’s Iszac Henig (who also swims in the female division, but identifies as male). Henig explained, “As a student-athlete, coming out as a trans guy put me in a weird position. I could start hormones to align more with myself, or wait, transition socially and keep competing on a women’s swim team. I decided on the latter.”

Although no one questioned Henig’s right to swim with women while identifying as a male, a firestorm of debate ensued over Lia’s victories. The NCAA defended Lia’s right to compete, while others, such as Olympian Caitlyn Jenner (formerly Bruce Jenner), argued that Thomas’s presence in the pool with women was unfair, would kill women’s sports, and is “not good for the trans community.”

As similar controversies erupted across the globe, female ath- letes who expressed their discontent about taking second place to such opponents were belittled as sore losers and transphobes. They were told that they need to quit overreacting; that the presence of a few trans athletes would not signal the end of women’s sports. However, the difficulty isn’t resolved because of the relatively small number of athletes who identify as trans. For example, in three years of competitions against two male runners who identified as female in Connecticut, nearly one hundred girls failed to move on to the next level of competition because they finished behind them. Furthermore, when a male competes as a female, he often removes a woman from the opportunity to compete.

Some of the consequences of men competing as women are more severe than the difference between a gold and bronze medal or missing out on a scholarship. Within the field of mixed martial arts, Fallon Fox, who identifies as a female, vanquished Tamikka Brents in two minutes, broke her eye socket, and left her with a con- cussion and seven staples in her head. After recovering from the injuries, Tamikka said, “I’ve fought a lot of women and have never felt the strength that I felt in a fight as I did that night. I can’t answer whether it’s because she was born a man or not because I’m not a doctor. I can only say, I’ve never felt so overpowered ever in my life and I am an abnormally strong female in my own right. Her grip was different, I could usually move around in the clinch against other females but couldn’t move at all in Fox’s clinch.” Rumors spread that Fallon Fox had broken two women’s skulls, and Fox tweeted, “For the record, I knocked two out. One woman’s skull was fractured, the other not. And just so you know, I enjoyed it.”

Some might retort that combat sports are inherently danger- ous, and those who compete in mixed martial arts are aware of the risks involved. However, combat sports often have a dozen or so different weight classes, ranging from strawweight to super heavy- weight. On the day before opponents face one another in the octa- gon, they weigh in to ensure that they aren’t one pound above their respective weight class (or half a pound for championship bouts). If they miss weight, they could be disqualified from competition. For a title match, they become ineligible to win the belt, even if their opponent should choose to continue with the fight.

Therefore, if a 265-pound heavyweight fighter weighs more than eight ounces above his weight class, this unfair advantage renders him ineligible to become a champion. For biological realities such as weight, age, or height, there is no psychological identity that overrides it. Because there’s no such thing as being trans-weight, a heavyweight fighter cannot identify into a different weight class to annihilate smaller opponents and take home their paychecks. Because it’s impossible to be trans-age, a thirty-year-old Little League coach cannot identify as an eleven-year-old and relieve the starting pitcher when his team is falling behind. However, if a man identifies as a woman, then regardless of any athletic advantage this might afford him, it is considered transphobic to question his “right” to compete against women.

Everything in sports—from the size and age of the athletes to their equipment and uniform fabric—is standardized to ensure that one opponent is not given an unfair advantage over the other. One USA swimming official, who resigned over the controversy regarding Lia Thomas, pointed out that “if a swimmer was wearing an illegal swimsuit, we would tell the swimmer ‘Go change your swimsuit. That’s not the right fabric. It’s giving you an advantage.’” But is there an objective athletic advantage to being male? Yes.

Men, on average, have 36 percent more muscle mass than women. They also have greater aerobic and anaerobic capacity, slow and fast twitch muscle fibers, and a larger heart.9 Their bones are shaped differently and are stronger than women’s. Because of women’s decreased ligament strength in comparison to males, females are five times more likely to rupture their ACL. Studies of grip strength also show that 95 percent of men produce greater force than 90 percent of females.

Many of these advantages are because the adult male body has been marinated for decades in levels of testosterone that are approximately ten times higher than a woman’s. In order to attempt to offset this advantage, the International Olympic Com- mittee required that male athletes who identify as women take tes- tosterone-suppressing drugs to bring their levels down to 10 nano- moles of testosterone per liter of blood for at least a year prior to competition. But since the average woman has between 0.5 to 2.4 nanomoles per liter, a male’s level of testosterone after suppression is still between four and twenty times higher! Even after a year of testosterone suppression, the typical male athlete only loses about 5 percent of lean body mass, muscle area, and strength.

This also does not account for the fact that testosterone levels fluctuate. Prior to competition, a man’s testosterone levels will spike in a manner that is more pronounced than in female ath- letes. Regardless of an athlete’s testosterone level on the day of competition, the physiological superiority of the male is largely due to the impact of experiencing puberty as a male, which cannot be reversed.

If testosterone alone could mitigate the differences between male and female athletes, women who identify as males would be flooding into male-dominated sports by taking testosterone supplements. But regardless of how much testosterone is injected into a woman, she will typically be unable to compete with male athletes at the same division. However, when a woman takes testosterone while transitioning, she becomes more likely to defeat the other female athletes.

The objective biological differences between men and women explain why in 2017, nearly 800 high school boys beat the women’s world record in the 100-meter sprint, and why the woman’s world record 400-meter race is bested more than 15,000 times per year by men and boys. It explains why Serena and Venus Williams were surprised, when they claimed that no man ranked outside of the top 200 in the world could defeat them, and an unknown but cocky, cigarette-smoking German tennis player who was nearing retirement volunteered for the challenge. Karsten Braasch said he prepared for the match with a few cocktails and a round of golf, and then defeated Serena 6–1 and Venus, 6–2. Serena remarked, “I didn’t know it would be that difficult. I played shots that would have been winners on the women’s circuit and he got to them very easily.”

Nonetheless, as the Williams sisters demonstrate, women are capable of extraordinary athletic feats. However, women can’t display their talents if they’re being beaten by average male athletes. There’s no need to think any less of their accomplishments because they’re not competing against males, though. This would be like devaluing the career of an undefeated boxer because he never fought an opponent who weighed ten pounds more than he did.

Although the debate over sports and gender identity is often framed around the subject of “trans athletes,” this isn’t the real issue. The issue is men competing in women’s sports. During competition, athletes do not compete against the internal sense of identity of the other person, but against the other person’s body. Therefore, in the spirit of true sportsmanship, one must admit that at least in the world of athletics, being female matters more than feeling female.

Read more on the Catholic perspective on gender in Male, Female, Other?:

Jason Evert addresses the most common claims of gender theory, including “How many genders are there?”, “Should I use their preferred pronouns?” and “What if I experience gender dysphoria?”, showing how to respond with charity and clarity.

Jason Evert addresses the most common claims of gender theory, including “How many genders are there?”, “Should I use their preferred pronouns?” and “What if I experience gender dysphoria?”, showing how to respond with charity and clarity.

If you care about someone who identifies as trans and don’t know how to respond, or you experience gender dysphoria and wonder what God’s plan is for you, you’ll find the answers inside.

Get your copy of Male, Female, Other? now.