This blog is extracted from our book Praying the Nicene Creed, which meditates on the Nicene Creed line by line.

I believe in one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church.

Lamentation at the “individualism” of the modern world has become so commonplace that it hardly seems there could be anything left to say about it. Most people tend to think of the purpose of their lives and what constitutes “happiness” as entirely up to the individual’s tastes or feelings. So much is this the case that a young woman once asked me a most curious question about heaven: “When we die and go to heaven,” she asked, “does each of us experience whatever we personally like the most? You have your bliss in heaven, and I’ll have mine?”

Far from being a way of imagining heaven, what she was describing would be the very essence of hell. To be turned in upon our own desires to the exclusion of all else would be hell. It would not be ecstasy, which means a going-out-of- oneself, but solitude and solipsism. Speaking of hell, Pope Benedict XVI once observed that it “denotes a loneliness that the word love can no longer penetrate and that therefore indicates the exposed nature of existence in itself ”. Alone in the dark, the child most desires a hand to hold. What we most desire is communion, and we can envision no true heaven that isolates rather than unites us with others.

This instinctive desire for union is bound up with the most ancient of philosophical and religious questions. As we discussed in the first chapter, reality is in some sense “one”, but in what sense exactly? Much of ancient oriental thought posits a simple oneness to which all individuation or difference is a mere illusion. The philosopher Parmenides brought this monistic claim to the Mediterranean world. All change is a mere appearance of a simple unified reality called “being”. “All is one,” he proclaimed, thus provoking Plato and Aristotle to spend their lives considering in what way he was right and in what way he was wrong. To be brief, they both affirm that individual beings are real – what could be more obvious? – but that by nature they participate in a grand and beautiful order called the cosmos. Each being plays its part in the order of being as a whole, and this is the way in which reality is simultaneously one and many.

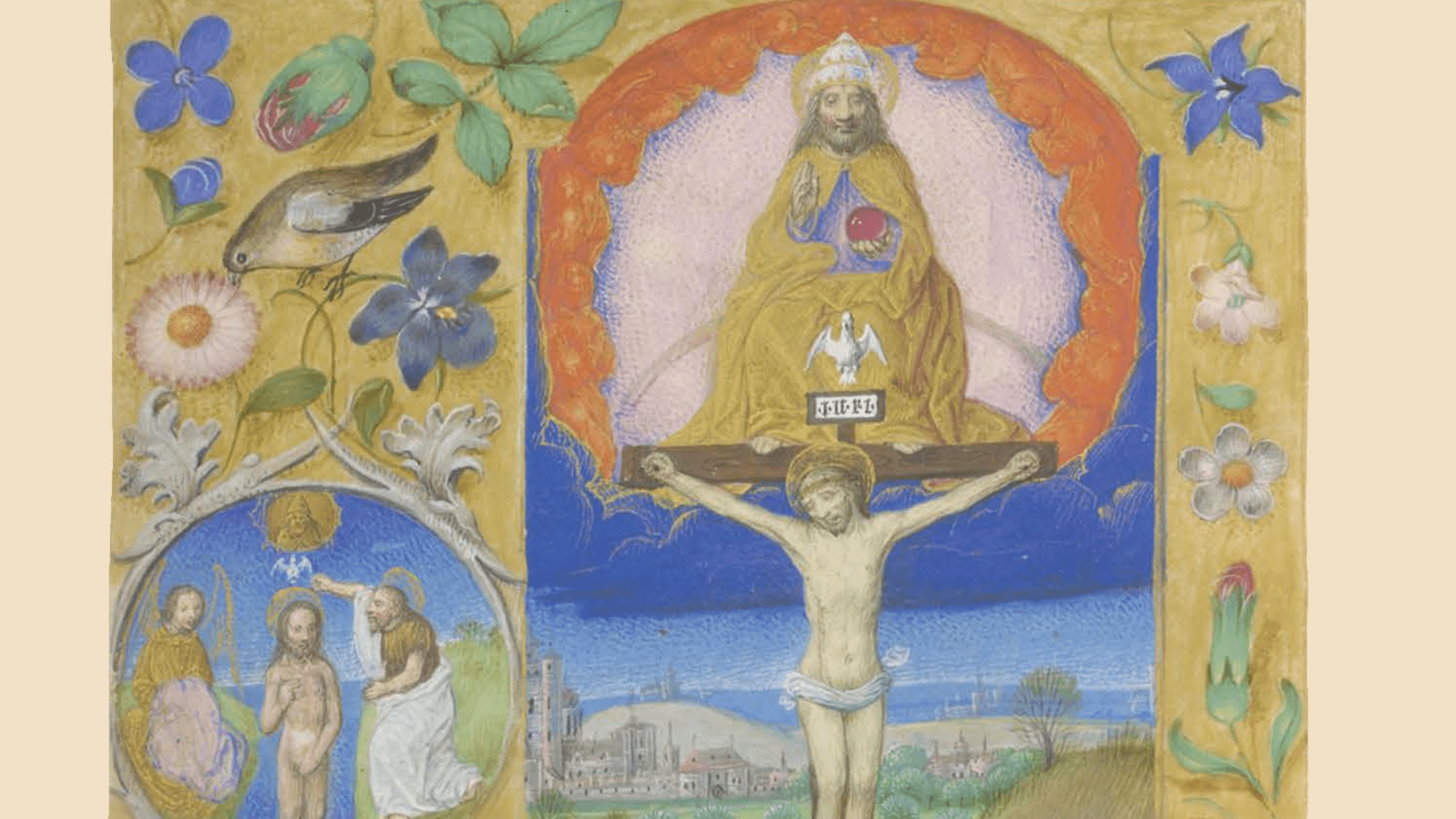

Christianity brings to that ancient philosophical vision an insight that deepens it beyond measure. God, as we have seen, is one, and yet he creates: he causes creation to be and, in calling it to be in itself, he causes it not to be God. God is eternal and must be, but all that is not God is contingent and brought into being by his act of creation. God’s act of creation puts all things in being, including time and the scattering winds of history.

God as creator is the first, the most fundamental, thing we know about him. To gather back to himself all that he has created, all that has been set in being, cast out, and scattered on the vicissitudes of time, God answered the primordial act of creation with two acts that bring creation to fulfilment.

First, he sent his son into the world to redeem all things from the loneliness of sin and recall them to their creator. Christ commands “Abide in me, and I in you”, for “I am the vine, you are the branches” (Jn 15:4-5). Soon after, he prays to the Father “that they may all be one, even as you, Father, are in me, and I in you, that they also may be in us” (Jn 17:21).

Second, to be made one with Christ is not to cease to be oneself, but to enter into communion with him. It is to become a member of his body, and his body is the Church. St Paul teaches that “we, though many, are one body in Christ” (Rm 12:5). To the Corinthians, he repeats that, just as “all the members of the body, though many, are one body, so it is with Christ. For by one Spirit we were all baptised into one body – Jews or Greeks, slaves or free – and all were made to drink of one Spirit.” (1 Co 12:12-13)

The difference between creator and creation is never to be overcome, specifically because God sees it as good that we should be at all and that we should be ourselves. Only in so remaining can we be reconciled to him and stand in permanent relationship of love to him; we would otherwise be swallowed in an abyss of oneness, no longer branches but simply reduced to the vine. G.K. Chesterton made this point nicely when he wrote: “But…this separation between man and God is sacred, because this is eternal. That a man may love God it is necessary that there should be not only a God to be loved, but a man to love him.” The eternal communion of that love is the Church herself, where we, the members of the body, are united to Christ, the head.

The modernist theologian Alfred Loisy may have been speaking ironically when he stated that Jesus proclaimed the kingdom of God, but what came was the Church. In fact, we should proclaim this in all sincerity. The second-century Shepherd of Hermas announces, “The world was created for the sake of the Church” (CCC 760). This is no fixation on a human institution, much less the worship of it; rather, it recognises that the deepest longing of our individual souls, our individual existences, is to enter into the abiding, everlasting communion that is membership in Christ’s body. Love is that deepest desire, and communion with love itself is not our oblivion but our fulfilment. Love, recall, is the heart of reality. The Church is the ongoing realisation of that fulfilment that will be brought to perfection at the end of time.

Because this journey to communion is still a state of pilgrimage, the Church must be recognised by four qualities that vouchsafe her integrity and guide her life.

Comprehending all the universe, the Church is one: one and practice of faith (CCC 815), and one as a society and government (CCC 816).

She is holy, not because her members are without sin, but because the entrance into communion with the Body of Christ is the only shattering of loneliness and only path to becoming one with the holiness of Christ (CCC 827).

She is catholic, or universal, insofar as the Church is the regathering to himself of all that God has made. All persons are called, but indeed all creation as well, for, as St Thomas Aquinas writes, every existing thing is good through its assimilation to God, who is goodness itself (Summa Theologica, I.6.4).

Finally, she is apostolic: the Church is founded on the Apostles and, through the abiding presence of the Holy Spirit of whom the Church is the temple, she remains “in communion of faith and life with her origin” (CCC 863).

All four of these qualities are outward indications of the abiding presence of the Holy Spirit, who unveils Christ to us and makes possible our communion with him as one body. They have sometimes been regarded as tests of the true Church, but are better understood as the effects of the indwelling of the Spirit. They are signs of the communion we seek with our deepest longing.

Meditate more deeply on the Nicene Creed

In Praying the Nicene Creed, poet, critic and scholar James Matthew Wilson considers each line of the Nicene Creed in turn, showing through stories, images and recollections that this prayer describes the living theological reality that is at the heart of personal devotion.

In Praying the Nicene Creed, poet, critic and scholar James Matthew Wilson considers each line of the Nicene Creed in turn, showing through stories, images and recollections that this prayer describes the living theological reality that is at the heart of personal devotion.

Pray the Creed with the same depth of devotion as the other ancient prayers of the Church by ordering your copy of Praying the Nicene Creed today.