The Seven Last Words of Our Lord have, from the sixteenth century, been the subject of meditations of Good Friday. Fr Lawrence Lew OP’s set of reflections, the first of which is presented here, was first preached in Holy Week of 2022, during the Rosary Shrine’s annual “Holy Week Retreat”.

The fourth word (see Mt 27:46):

To God, his Father:

My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

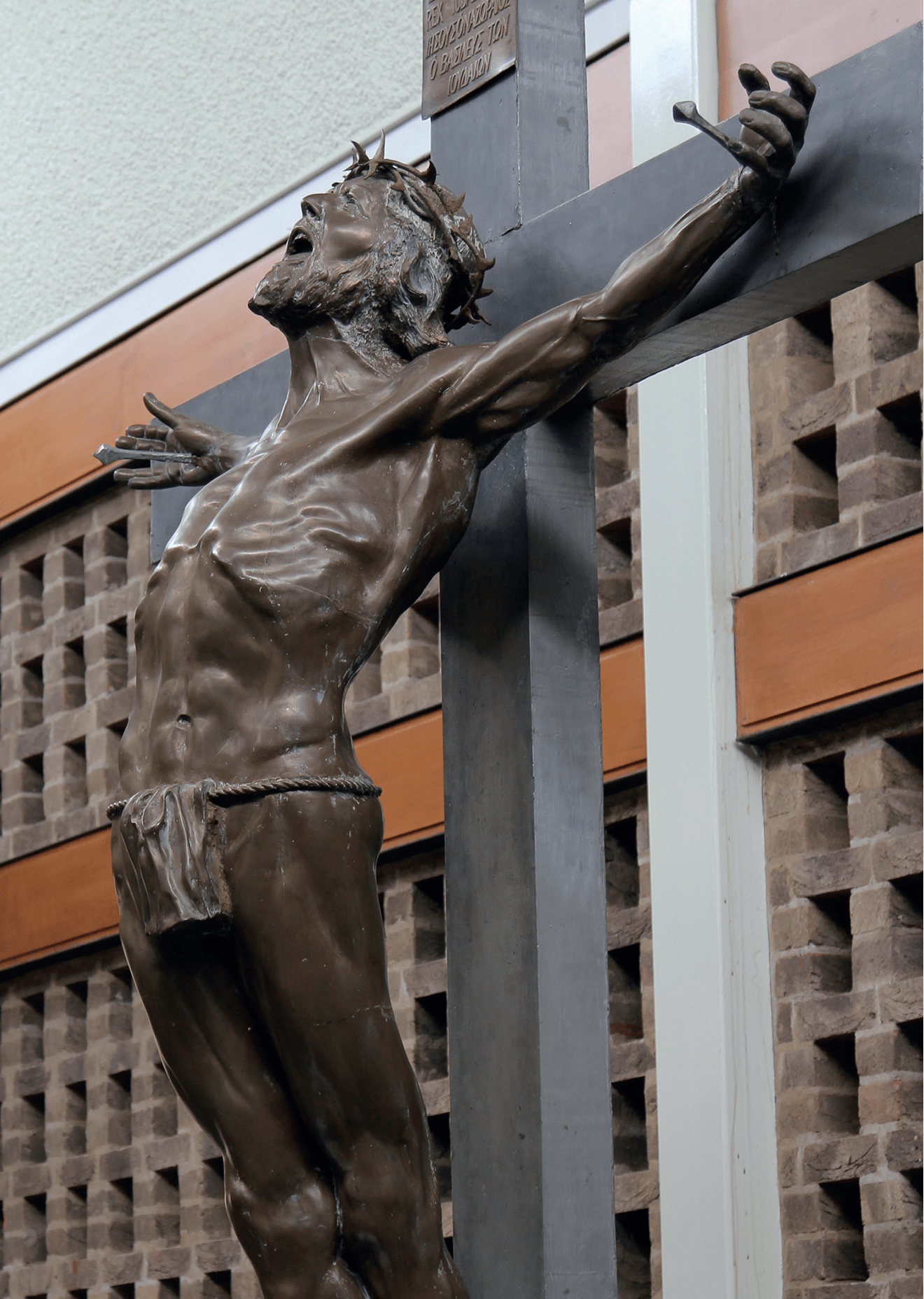

On Palm Sunday last year, my classmate from primary school, whom I have known since I was six but had not seen in over thirty years, was visiting London from Korea, and came to our Solemn Mass that day. The response to the responsorial psalm that day was this, the fourth word of Christ from the cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” It is, of course, also the opening lines of Psalm 21, a psalm attributed to King David. After the Mass, as he was waiting for his cab, he said to me: “I have never really understood those words of Jesus. Why did he say, ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’” What answer could I give in the one minute before his cab came? I told him, briefly, what I will expand upon now: Christ, the Second Person of the Trinity, is, of course, never separated from nor abandoned by the Father. This would be impossible. However, in becoming man and sharing our human condition, God willed and lovingly chose to share our human experience down to the very depths and dark pits of depression that we can experience. On the cross, Christ endures not only bodily pain but also the sufferings of the soul, psychological pain. Indeed, as St John Henry Newman says: “It was not the body that suffered, but the soul in the body; it was the soul and not the body which was the seat of the suffering of the Eternal Word.” Thus, Jesus says in Gethsemane: “My soul is very sorrowful, even to death” (Mt 26:38), and this mental anguish is so great that the Evangelists note that Jesus sweats blood. This is a rare medical condition called hematidrosis, and it is caused by extreme distress or fear, feelings our Lord experienced as he began to undergo his passion for our sake.

On the cross, when the crucified Lord utters these words, he expresses, as “true man” and as the Head of humanity (see 1 Co 11:3), the fullest extent of the psychological sufferings that human beings can experience. In permitting himself to endure everything that we human beings have to endure, so Christ chooses to share this deepest of existential pains: the sense of being alone, without a loving father, or even a loving God. Indeed, to think that there is no God, to truly be an atheist, creates a deep sadness of soul that can depress and warp a whole society. But even here, in this deep sorrow, a sorrow very much of our times, Christ our God wills to be present. Christ lovingly chooses to suffer this sorrow with us; with atheists; with those who have been abandoned by a parent; with people who do not experience God’s love and closeness; with those who cannot pray and are sorrowful as a result; with those who might, in times of sickness, distress and grief, feel that God is absent; with all who are confounded by the world’s terrors and uncertainties and heartaches, and who wonder: “Where is God? Why has he forsaken or abandoned us?”

Jesus, however, is not aloof from this existential angst. He is not distant and uncaring of our anguish. For here on the cross, he cries out and gives voice to the deep sorrow of soul that afflicts so many of our contemporaries, and that perhaps also gnaws at us. But Jesus cries out with these words of Psalm 21, which thus remind us that this feeling of the absence, the forsakenness, of God, is an experience that great religious men, such as David and Job, have all endured. These holy seers of times past have stared into the abyss, confronted the silence, and they all point to this moment of the cross, to Jesus who calls out, giving voice to the deepest sorrow of the human heart: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

Can you see the profound love and compassion of Christ? He so desires to show us that he is Emmanuel, God- with-us, that he wills even to undergo this anguish with us. He is not play-acting, but, in his humanity, freely willing it; Christ really does feel as we sometimes feel: abandoned by God. Except that now, even in those depths of depression and angst, we cannot any longer be abandoned by God. Through his crucifixion, Christ is now evermore there with us in our forsakenness. Therefore the psalm (139) rightly says: “O where can I go from your spirit, or where can I flee from your face? If I climb the heavens, you are there. If I lie in the grave, you are there.” For “even darkness is not dark for you and the night is as clear as the day”. Where, then, is God? Right there, with us, with you, in the darkness!

Cling to these words of the Lord, hold on in your minds to this bitter moment on the cross. Then, in the darkness, in those times when you feel as though you are lying in your grave, remember that Christ too endured this sense of being abandoned by God, and that he lovingly chooses to enter into our darkness in order to make it “as clear as day”. For his presence is the light; he is God-with-us.

Let us end with the prayer that the Angel of Peace taught to the holy children of Fatima:

“My God, I believe, I adore, I hope and I love Thee! I ask pardon for those who do not believe, do not adore, do not hope and do not love Thee.”

This reflection is extracted from our book Lenten Devotions: Stations and Meditations from the Rosary Shrine. Fr Lawrence Lew OP offers three powerful Lenten devotions: Stations of the Cross featuring photographs and meditations, the Canticle of the Passion based on words revealed to St Catherine de Ricci, and recollections on the seven last words of Jesus on the Cross.

This reflection is extracted from our book Lenten Devotions: Stations and Meditations from the Rosary Shrine. Fr Lawrence Lew OP offers three powerful Lenten devotions: Stations of the Cross featuring photographs and meditations, the Canticle of the Passion based on words revealed to St Catherine de Ricci, and recollections on the seven last words of Jesus on the Cross.

Find more powerful Lenten devotions and reflections, and support the mission of CTS, by ordering your copy of Lenten Devotions today.